B is for Bind

by Doris Leibold in A - Z of Clean, Clean Language, Metaphor, Symbolic Modelling, Systemic Modelling

The protagonist of every hero’s journey at some point faces a difficulty for which there is no immediate, easy solution. Very often, the type of difficulty preventing the hero or heroine from making progress is a bind.

As coaches, facilitators and therapists we are often witness to our clients’ struggles on their heroes’ journeys and it can be useful to know the kinds of forces at play within binds so as not to get tangled up in the client’s problem while trying to help them get out of it. This blog post hopes to provide some useful pointers for how best to support your clients when they are in binds so they can move towards getting more of what they want.

What is a bind?

In the context of Symbolic and Systemic Modelling, at the most basic level, the word bind is an informal expression and metaphor for a difficult or annoying situation. This seemingly simple definition might have us believe that a bind, while an unpleasant experience, is straightforward enough. On closer inspection, however, it turns out there is more than one layer that is worth exploring and what follows is an attempt at separating out what’s what and what we can do as facilitators in the different scenarios.

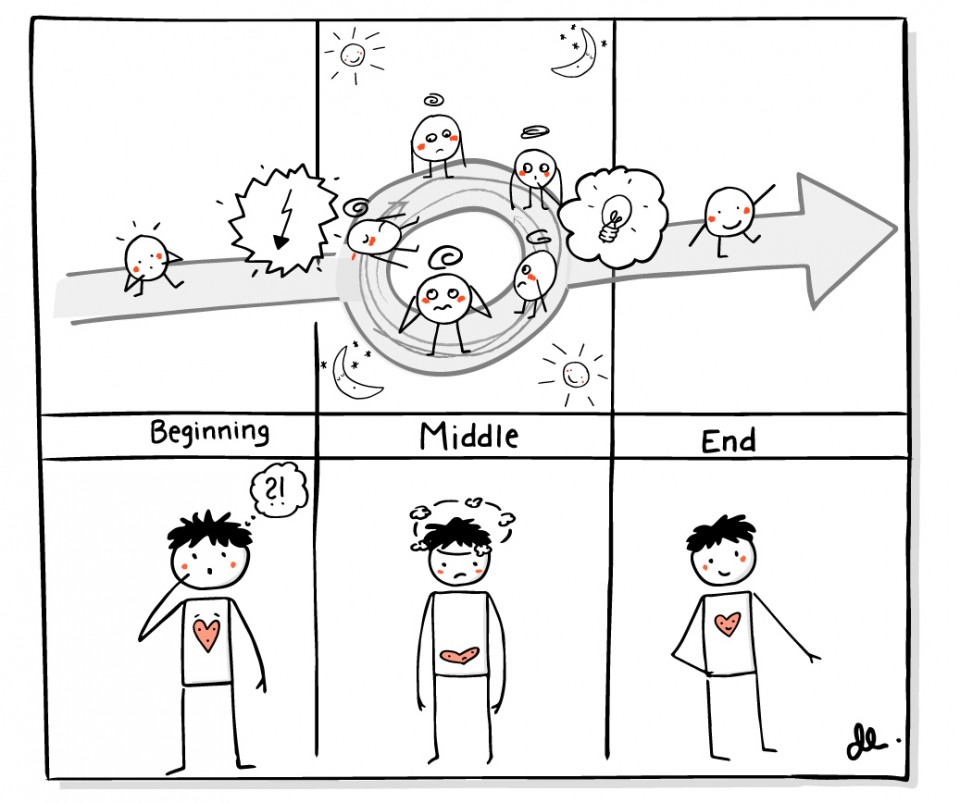

In Symbolic Modelling, building up from the simplest form to the most complex (from the client’s perspective), we can differentiate between three types of binds:

- A difficult situation with a beginning, middle and end

- A process (or a pattern) – without a clear beginning or clear end – that keeps happening

- A binding force that keeps a binding process happening

Bind 1 – A situation with a beginning, middle and end

At this level, the word ‘bind’ is a term used for a type of problem that is often accompanied by circular thinking and intense unpleasant emotions and cannot be solved by thinking or doing alone.

When someone is ‘in a bind’ it means they are in a situation where they do not know what to do because of a perceived lack of options or a ’real’ sense of choice even though choice may be logically possible (see “Pragmatics of Human Communication” by Watzlawick, Beavin and Jackson, 1967). When we hear a person say ‘I feel like I don’t have a choice’ what it very often means is that they are unhappy about the available options. The impact this kind of situation often has on a person is that they feel stuck and helpless. These kinds of binds are commonly experienced problems that are part of everyday life.

It is probably because being in a bind often comes with an unpleasant state of confusion, frustration, worry or distress, that the experience lends itself well to metaphor. Many expressions exist that nicely illustrate the predicament, such as:

- I’m between a rock and a hard place.

- Damned if I do, damned if I don’t.

- It’s a choice between the devil and the deep blue sea.

- It’s like going round in circles.

- We’re back to square one.

- I’m banging my head against a brick wall.

- It’s a Catch-22 situation.

- It’s like getting blood out of a stone.

- It’s a vicious circle.

- I’m in a tight spot.

- Whatever I do I just can’t win!

These are eleven different metaphors for the same kind of experience of not knowing what to do and there are probably many more (with a rich variety in different languages).

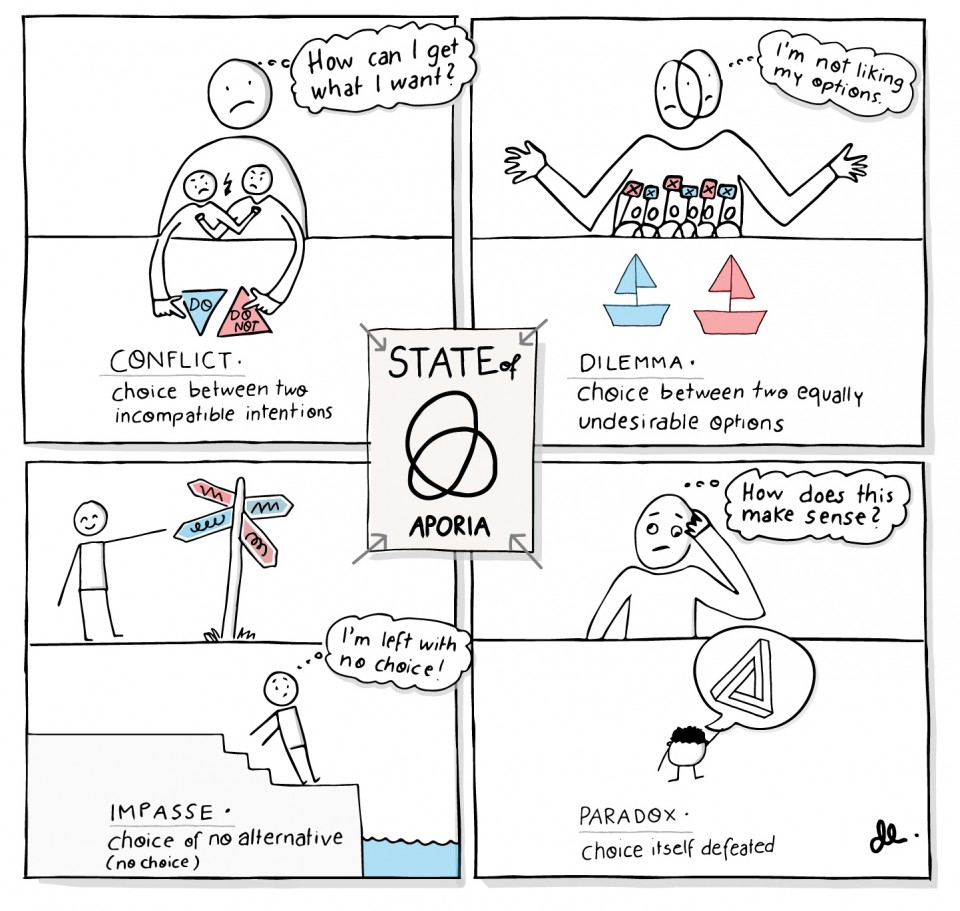

Penny Tompkins and James Lawley in Metaphors in Mind (page 182) have identified that at a higher level of abstraction these types of problems (or problem states) usually belong in one of 4 categories (each representing a different kind of structure of stuckness):

- Conflict

- Dilemma

- Impasse

- Paradox

It is important at this point to note that what’s a bind for one person might not be for another. Binds are always situational and as facilitators we need to be mindful to consider the situation from the client’s perspective. It is only from within the client’s own logic that what they are experiencing can be defined as a bind or not. It may not seem like a problem to us as we can see a choice where the client cannot (you may catch yourself thinking – Why don’t they just …?). Likewise, what we think could be a bind may very well turn out not to be for the client.

What makes something a bind for someone is the relationship they have with their options – or perceived lack thereof – in a given context and whether this somehow prevents them from getting (or even knowing) what they want.

In the best of cases, a client who is in such a bind manages to solve the problem and move on. As clean facilitators our job in these situations is to model the various options and to ask: “And when it’s like that, what would you like to have happen?” or “And when A and B – what would you like to have happen?” An example might be a classic case of incompatible intentions: “When part of you wants to stop smoking and part of you doesn’t, what would you like to have happen?” Or when someone faces a choice between two equally undesirable options: “And when you don’t like either option, what would you like to have happen?”

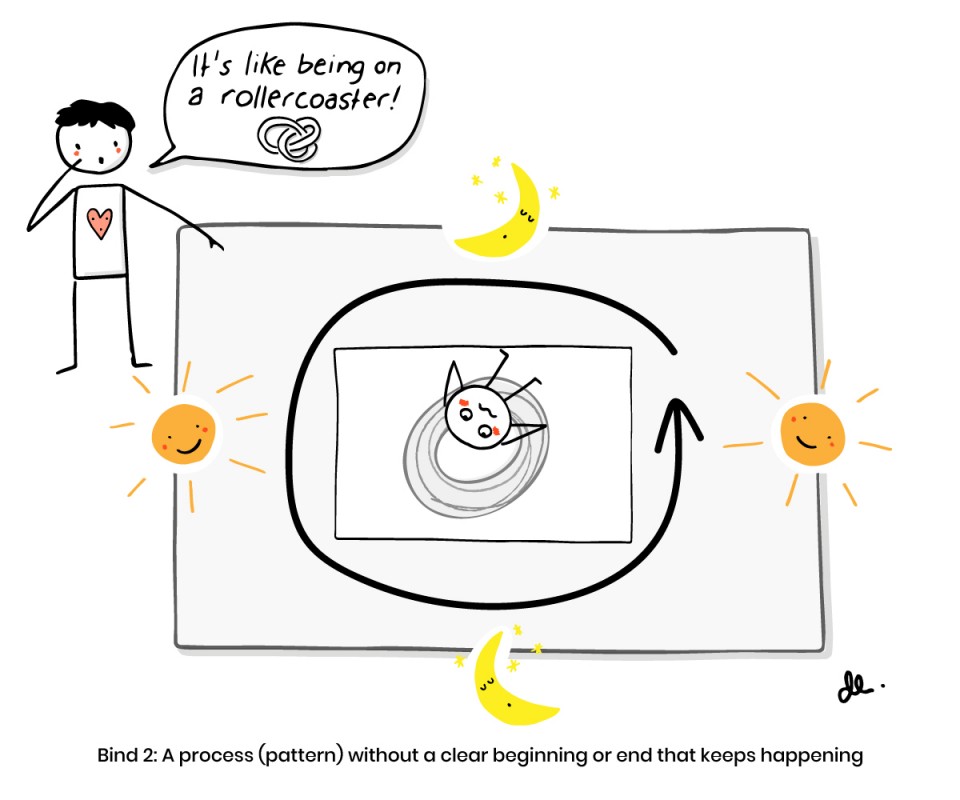

Bind 2 – A process without a clear beginning or clear end that keeps happening

But suppose a person repeatedly finds themselves in situations like these? When, no matter what they do, they keep having the same kind of experience over and over again and their way of responding remains the same? How would it be if this is ‘the story of their life’? Then a bind becomes more than an awkward situation, it becomes a continuously repeating awkward situation over a longer period of time – a binding pattern.

In Symbolic Modelling, the word bind may then not only refer to a single incidence of this type of problem but also to an ongoing pattern of behaviour in the face of the same type of problem. Thus bind is also:

… a generic term for any repetitive self-preserving pattern which the client has not been able to change, and which they find inappropriate or unhelpful.

Metaphors in Mind, p. 36

The language someone might use that will indicate the presence of a binding pattern can be subtle or initially not even noticeable, depending on how conscious someone is of their predicament. They may say:

- I keep getting/having … and I can’t figure out why.

- I keep on …

- This is the story of my life.

- Here we go again!

- This is nothing new.

- I’m having déjà vu.

- Hm, this is interesting, it feels like we ended up where we were in the last session.

Here’s an example: If a client has a tendency to join different groups and get many projects going at the same time, they may also have a tendency to become overwhelmed and then when the overwhelm gets too much they will likely jettison some of their projects and ideas until they find themselves having new ideas and getting new projects started again and so they continue repeating the same cycle over and over again. At the start of a session, such a client may talk about their current incident of overwhelm, but as the session progresses, they are likely to say something like, “I want to do new projects and I want to stop being overwhelmed by them! And this is nothing new. I always take on too much and it always results in overwhelm – then I clear the decks, and then it starts again.”

Once we begin to understand that a client is in a binding pattern like this, we can invite them to pay attention not only to the details but the ongoing nature of the pattern - the big picture - and ask them, “And when you always take on too much and it always results in overwhelm, and you clear the decks then it starts again – that’s always too much and always overwhelm, clear the decks and start again – like what?”

And the client may then offer a higher-level metaphor such as, “Like being on an everlasting rollercoaster with constant ups and downs.”

We can then develop ‘rollercoaster’ and follow up with, “And when it’s like that, what would you like to have happen?”

The purpose of this line of questioning is to allow the client to gain insights from a higher level of abstraction, a higher vantage point from where they can have more awareness of all the elements that keep the pattern going.

If they can recognise their own pattern and what keeps it alive, they may well find a new outcome, a place of acceptance of the pattern, new options or even new organising metaphors which may lead to important shifts in their lives, personal growth or even transformation.

Bind 3 – A binding force that keeps the binding process happening

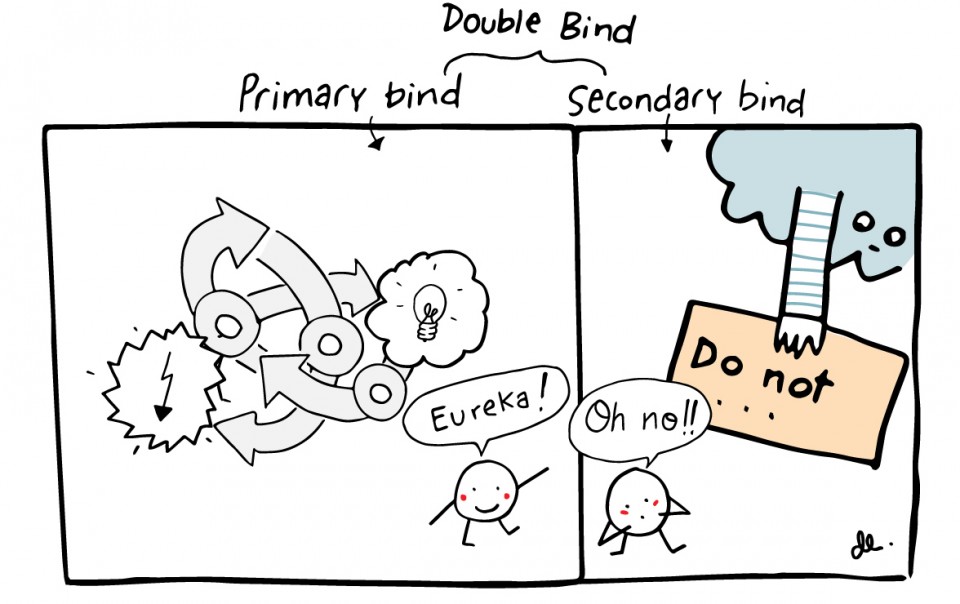

But what to do when that (i.e. bind 2) isn’t awkward and unpleasant enough? What if the client’s struggle not only consists of a single bind, or single binding pattern, but there is a secondary binding force – usually at the level of beliefs – stopping the binding pattern (or primary bind as we might call it) from resolving? Then the client would truly face a hero’s journey that might get worse before it gets better. This may become apparent later on in a session or only over a series of sessions. We would code this escalation as a ‘double bind’ or double binding pattern. When they appear to have found a solution to the primary bind, a secondary bind may come as a belief such as “But I’ll be bored if …”, or an injunction such as “Do not stop learning” or “Don’t be lazy” that prevents the client yet again from getting out of their unhelpful pattern.

Where does the word ‘bind’ come from?

The noun bind meaning "anything that binds," in various senses, is derived from the verb bind (v.) which can be traced back to Old English bindan "to tie up with bonds" (literally and figuratively). The meaning "tight or awkward situation" dates back to 1851.

A bind can usefully hold something firmly and securely in place by intentionally restricting movement and flexibility. And in fact, there are plenty of things that bind us that serve us well – agreements and contracts are drawn up for this very purpose. And we’re bound to do certain things because we want to be successful and just because we are who we are. Depending on context and who or what is being bound, however, a bind – or rather the effect of it – can be help or hindrance. This is especially true for the figurative use of the word which has taken on the meaning of “tight or awkward situation” and which provided the springboard for this article.

The way we use the expression ‘double bind’ in this work can be traced back to Gregory Bateson, the anthropologist, cyberneticist and systems thinker whose work had a significant impact on the developers of NLP. Bateson and his colleagues developed the double-bind theory of schizophrenia in the 1950s and this theory subsequently served other thinkers, in our case James Lawley and Penny Tompkins, in developing ways for how to deal with psychological problems that have a bind-like nature.

What about binds in teams?

“A bind in a system of individuals”, Caitlin Walker tells me, can be “where a system is attempting a solution but the attempt at the solution in itself is recreating the problem, usually through misunderstanding. And the more effort they put in, the harder they work, the worse it gets.” Asked about where binds start, Caitlin responds: “They often start from three things: diversity, contempt, misunderstanding.” If we respond to differences with contempt, then misunderstandings and drama are perpetuated and any genuine curiosity for inquiring into one another’s experience gets bound.

Let’s look at two examples Caitlin shared with me and what you can do as a clean facilitator.

A CEO of a company may want their team to be self-organised. In order for the team to be self-organised they need to be trusted and appreciated and led with a hands-off approach but in order for the CEO to trust them, the CEO needs to know lots and lots of detail. When the CEO asks for lots of details, however, the team members do not feel trusted and stop making decisions for themselves. Together they are trying to resolve their problems but the method for resolving the problems is holding the very same problems stable.

Two people in a business partnership may be classic rescuers and what’s important for both of them is taking care of well-being. Each of them tries to take work off the other when they think the other is working too much. However, when person A takes work off person B, person B cannot think, “Oh great, work is being taken off me, I can relax” but instead sees that person A is working too hard and thinks, “What can I do to take work off my partner?” As a result, both end up working longer hours. Everything they each do to create well-being for the other is actually making things worse. And worse still – they may each start resenting the other for not noticing that their partner is working too hard.

There are many options for how we can work with teams in binds and they will be informed by the contract we have with them, and the information gathered during Clean Scoping. One way of supporting the team in example A would be to ask the team: “When CEO needs a lot of detail and you need to be free to make your own decisions … what would you like to have happen?”

In the case of example B when we have figured out the patterns playing out between the two partners, we may decide to point it out and say, “Shall I tell you what I’m noticing? Every time person 1 sees person 2 work too hard, person 1 takes on more work and person 2 ends up working more. When it’s like that, what would you like to have happen?” Or we could create a starting frame that tries to go beyond the bind: “When you are taking care of your own well-being at your best, that’s like what? How would you like the other person to support you in your own well-being? What would someone see or hear if you are not taking care of your well-being?”

By introducing them to the Systemic Modelling models (e.g. Clean Feedback, Developmental Tasks, Clean Set Up) and showing them how they can separate evidence from inference, teams can gain a language for how they can talk about what they want, what they will see and hear when they have it and how others can support them. “All systemic models are designed to achieve more congruence between what ‘an individual’s system’ or ‘a system of individuals’ would like to have happen and the way they go about achieving it,” says Caitlin.

A philosophical approach

In philosophy, the experience of not knowing what to do, the state of uncertainty, confusion, puzzlement, ’stuckness‘ goes by the name of aporia which is Greek and literally means: lacking passage. Approached from this angle, we could say a bind is a state of confusion arising out of a difficult situation with seemingly impossible choices. And this also explains what it very often is that is being bound: our thoughts and feelings and consequently our capacity to make good decisions. Viewed from this angle, the four categories of binds mentioned earlier seem like gateways to states of aporia. This makes me wonder about the widespread use of paradox in various spiritual teachings – is this because they provide an opportunity for the mind to learn how to relate to life’s contradictions?

What can you do when you don’t know what to do?

The trick with binds may be to approach them not as problems to be solved but problem states to be broken and problematic patterns to be interrupted. This is more likely to happen when we can bring awareness to what is going on. If we as facilitators want to support clients in becoming aware of what is going on for them it is essential to have awareness of our own binds and the topic in general. Here are some ideas for what you can do if you’d like to spend some time exploring the topic further:

- Get to know your own binds and your patterns of responding to them – What typically puts you in a bind? How do you know you are in a bind? What are your signals? And when you are in a bind, you’re like what? How would you like to be?

- Get to know your signals for knowing that your client is in a bind – What lets you know?

- For a lyrical and very visceral experience of what it’s like to experience a bind, read R. D. Laing's ‘Knots’

- Another poetic expression of (how to get out of) a bind is Portia Nelson’s poem Autobiography in Five Short Chapters

- Examples of wisdom stories that deal with paradoxes or seemingly unreconcilable contradictions can also be found in Japanese koans or the Chinese Tao Te Ching.

- Wikipedia provides a rich overview of paradoxes from from Maths to Mysticism.

- For a more artistic take check out some of M.C. Escher’s work (especially those under Impossible Constructions, Mathematical, Transformation.) Can you find appreciation for them?

For more in-depth reading material from ‘clean’ sources:

- Metaphors in Mind (especially 181 ff.)

- Clean Approaches for Coaches (pages 174-194)

- What are Double Binds?

- Modelling the Structure of Binds and Double Binds

What do you know now about binds?

I, for my part, know that binds are part of the human experience that seem to offer a chance for transformation like no other kinds of problems. They seem to be the riddles that many princes and princesses, lovers, monks, mystics and seekers of all kinds throughout the centuries and across cultures have had to solve on their spiritual journey and quest for the meaning of life. Looking back on my own life’s knots, tangles, fankles, impasses, disjunctions, whirligogs, binds – as R. D. Laing referred to them – I can see now how they were invitations to change my way of thinking about something so that I could grow. And then there was something that Caitlin said in our conversation that struck a chord: binds are largely self-made problems. Realising that the binds in my life are partly of my own making allows me to see how I can create choice and arrive at a way of being where I am more at peace with the world and myself more of the time.

And what about you?

A massive thanks to Marian Way, James Lawley and Caitlin Walker for generously sharing their time, experience and expertise and providing valuable research pointers; to Julian Burton for his words of encouragement throughout the process of writing and adjacent conversations; and to Karrie Shield for her diligent proofreading and final edits.

Related courses

About Doris Leibold

Doris has trained in Clean Language, Symbolic and Systemic Modelling and holds the ACC level of certification with the International Coach Federation (ICF). She delivers Clean trainings and workshops in German and runs a monthly Clean Circle in Munich where she holds space for an open group to experience Clean Language by way of exploring common values and approaches to life.

With a background in non-violent communication and mediation as well as plenty of experience on the drama triangle, she is passionate about sharing tools and strategies that enable people to stay empowered in difficult situations and make decisions that are in line with their values.

Clean Language for her is like the master key to all of life’s questions, unlocking access to the next level of knowing. She loves to show others how they can use this key in their own life to their own benefit.

Doris trains on our 1-Day Introduction to Clean Language and our Clean Coach Certification Programme as well as hosting our 1-hour Clean Language Tasters and our series of A-Z conversations.

- Blog categories

- A - Z of Clean

- Adventures in Clean

- Book Reviews

- Business

- Clean Ambassadors

- Clean Interviewing

- Clean is like ...

- Clean Language

- Clean Language Questions

- Clean Space

- Client Stories

- Coaching

- Creativity

- #DramaFree

- Education

- Health

- ICF

- Life Purpose

- Listening

- Metaphor

- Modelling

- Outcomes

- Practice Group

- Symbolic Modelling

- Systemic Modelling

- Training